“Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.”

Joni Mitchell, “Big Yellow Taxi”

We rely on our chemical senses – smell, taste, and chemical feel – to protect us from harm. Smell natural gas? There may be a dangerous leak nearby. Milk tastes ‘sour’? It could make you sick. Eyes stinging? Consider moving farther away from the bonfire.

When our senses function properly, we barely notice them. However, as Joni Mitchell points out, we often don’t appreciate something’s significance until it’s gone.

And as some people unfortunately learn, when their chemical senses fail, their health also suffers.

Monell researchers have been investigating problems in the chemical senses for nearly fifty years, a legacy that now continues with the upcoming generation of scientists: Two postdoctoral fellows focus their research on how taste and smell disruptions affect people’s health and well-being.

Enlisting the Tongue to Improve Life for Cancer Patients

Each year, head and neck cancers affect over 500,000 people worldwide. These include cancers of the throat (pharynx), voicebox (larynx), and oral, nasal, or sinus cavities. Treatment usually involves surgery, followed by either radiation or a combination of radiation and chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, due to the location of many head and neck tumors, even targeted radiation often damages normal taste tissue, leading many patients to experience problems with their sense of taste.

Alissa Nolden, PhD

Alissa Nolden, PhD

Alissa Nolden, PhD, understands that oncologists sometimes consider taste loss a minor side-effect of cancer treatment. However, she notes that taste loss can cause more pressing issues, including weight loss and malnutrition.

“Problems with a patient’s ability to taste can lead to clinical setbacks,” says Nolden, who holds a dual doctorate in Food Science and Clinical Translational Science and is mentored by Monell behavioral geneticist Danielle Reed, PhD. “If a patient’s appetite suffers because of taste loss and they lose too much weight, their doctors may switch to a lower dose of treatment or pause therapy altogether. We want patients to receive the most effective cancer treatments, which means we need to learn more about radiation-induced taste loss.”

Nolden is collaborating with oncologists and nutritionists at the University of Pennsylvania to compare the effects of two different radiation therapies on taste tissue and perception.

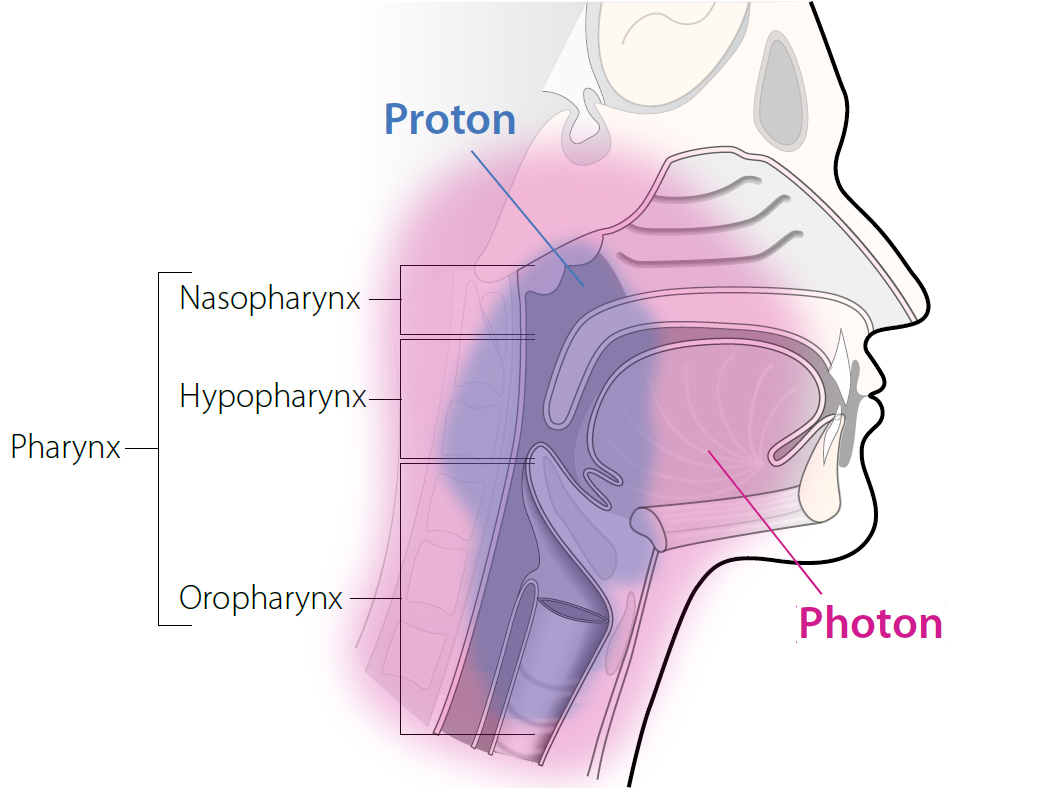

MORE ABOUT RADIATION THERAPY: Nolden’s study focuses on two forms of radiation therapy: “photon therapy,” which delivers x-rays and gamma rays to the tumor; and “proton therapy,” which uses positively charged sub-atomic particles instead.

Proton therapy, a newer option, administers radiation more precisely than the older treatment, and physicians believe it causes less damage. However, not many studies explore the clinical benefits of proton therapy over photon therapy, especially as they relate to taste loss.

Target areas of each of the two kinds of radiation included in Nolden’s study

Target areas of each of the two kinds of radiation included in Nolden’s study

Beginning next year, Nolden will evaluate patients with head and neck cancers before, during, and after they undergo one of the two radiation therapies.

Over the course of treatment, she will measure changes in patients’ perceptions of the five taste qualities (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami), as well as of the chemesthetic compounds capsaicin and menthol (which your chemical sense interprets as burning and cooling, respectively).

As lead investigator on the multi-site project, Nolden recently applied for research funding from the National Institutes of Health. Where previous studies have relied on patients to self-report, Nolden intends to use more quantitative testing methods, such as the well-established general Linear Magnitude Scale. This will generate more reliable data, especially since people often confuse the sense of taste with the perception of flavor.

Nolden is also partnering with University of Pennsylvania oncology nurses and clinical dieticians, who provided valuable feedback as she designed the taste tests to be both palatable and scientifically useful. Nolden predicts that data from this study could some day help hospital staff identify foods that are more tolerable to those undergoing cancer therapy.

“What we know so far about cancer treatments and their effect on taste is mainly anecdotal,” Nolden said. “With more quantitative taste data, physicians may be able to better preserve their patients’ sense of taste, and dieticians could develop meals that patients are likely to accept. I plan to continue working closely with clinical providers to help their cancer patients avoid detrimental weight loss.”

The Trouble with Breathing

Picture this: you’re walking by a fragrant garden, and you suddenly suffer an uncontrollable coughing fit. Now imagine that incidents like these often make it hard for you to breathe, and your doctors have been unable to help you.

Unfortunately, some people don’t have to imagine this scenario.

An estimated 22 percent of people admitted to the emergency room for shortness of breath have what’s known as “vocal cord dysfunction.” And roughly half of these patients report that an odor triggered the episode.

Carolyn Novaleski, PhD (photo credit: Anne Rayner; VU)

Carolyn Novaleski, PhD (photo credit: Anne Rayner; VU)

“Patients experience these breathing or coughing episodes at different severity levels, but it’s common for patients to explain that they don’t want to leave the house for fear that smelling an odor or chemical will trigger an episode,” said Carolyn Novaleski, PhD. “It can significantly disrupt their lives.”

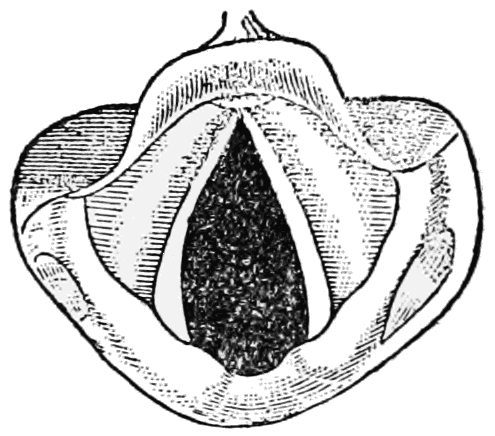

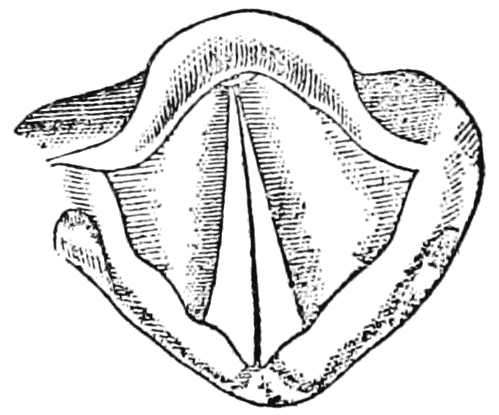

MORE ABOUT VOCAL CORD DYSFUNCTION: When people with vocal cord dysfunction suffer a breathing episode, their two vocal cords inappropriately close during inhalation (see the images below). Patients often feel like they’re suffocating, even though in most cases some air can still squeeze through a small opening between the vocal cords.

Behavioral therapy, where patients learn breathing exercises to keep their vocal cords open, is generally successful in improving symptoms. However, because vocal cord dysfunction often mimics other breathing problems, it can take years for a patient to be correctly diagnosed.

|

|

|

Open vocal cords as seen during normal inhalation |

Closed vocal cords as seen during a vocal cord dysfunction episode (or normally when speaking) |

With a clinical background in speech-language pathology and a doctorate in Hearing and Speech Sciences, Novaleski’s earlier research into vocal cord function and structure makes her uniquely qualified to investigate how the chemical senses may exacerbate this disorder.

Studying vocal cord dysfunction presents a number of challenges. No standardized method currently exists for preparing and delivering airborne stimuli to these patients, and there are only limited ways to measure upper airway irritation. Working with mentors Pamela Dalton, PhD, and Joel Mainland, PhD, Novaleski plans to implement protocols generally used in chemical senses research and sensory psychology – such as human psychophysical measures – to overcome these limitations. Novaleski is also working with collaborator Karen Hegland, PhD, from the University of Florida, to measure vocal cord closure during cough, another common symptom in people with vocal cord dysfunction.

In consultation with her mentors and with ear, nose and throat specialists, Novaleski decided to focus her initial efforts on healthy volunteers in order to provide a baseline for future studies with vocal cord dysfunction patients.

She plans to measure volunteers’ breath and cough airflow and upper airway sensory irritation during exposure to an airborne irritant. She will then lead each volunteer through a behavioral breathing intervention, and expose them to the irritant again. Novaleski’s goal is to determine if irritant-induced coughing and sensory irritation can be modified by retraining people’s breathing patterns.

“Collecting objective measurements from healthy volunteers will facilitate later studies with vocal cord dysfunction patients,” said Novaleski. “Long-term, I hope to better define the scope of this disorder. Ultimately, a more precise definition for vocal cord dysfunction will reduce the time it takes to diagnose and prescribe appropriate interventions.”

She also hopes her testing procedures will ultimately inspire more researchers to target vocal cord dysfunction.

From Lab to Clinic

For Reed, co-chair of Monell’s Postdoctoral Training Program, both projects exemplify the potential benefits of integrating fundamental chemical senses research and clinical studies.

“These two projects represent exciting examples of using emerging pathways in taste and smell to understand human disease,” said Reed. “At Monell, we have seen time and again how knowledge derived from basic science studies drives human research into new areas. I see Dr. Novaleski’s and Dr. Nolden’s studies as high-quality templates for the continued expansion of Monell’s mission into medically-relevant research.”

By studying clinical problems involving taste and smell, Nolden and Novaleski are affirming yet again how important the chemical senses are to health and well-being. And their passion is evident when they speak about their research – each scientist fervently hopes her study will help lead to innovative patient care.

“This work will hopefully provide oncologists with additional, useful tools to help treat their patients,” said Nolden. “We all want each and every patient to achieve their best possible outcome.”

Novaleski agrees. “I developed the habit of referring to ‘our patients’ because I feel as though clinicians and researchers are on the same team,” she said. “Ideally, collaborations like these will significantly improve patient quality of life.”