Pamela Dalton, PhD, MPH is an experimental psychologist, blending her training in public health and chemosensory science. She studies how emotions and thought patterns affect the way people perceive odor and sensory input from their surroundings – including the food, flavors, and fragrances we experience every day. When the Centers for Disease Control announced in Spring 2020 that the sudden loss of taste and smell is one of the six primary symptoms for COVID-19, Dalton immediately began designing and administering smell tests related to possible infection with the novel coronavirus.

Q. Your COVID-19 smell study-by-mail is currently the only active human participant project open on the Monell website. How does it work?

A. This is a test of the sense of smell that you can perform at home, as it relates to flu, COVID-19, and other respiratory viruses. We are hoping to learn whether COVID-19 infection impacts your ability to smell more than other respiratory viruses. Participants receive in the mail a set of scratch-and-sniff odor cards with instructions for the sniff test and how to access the website where they submit their answers. It takes about 20 minutes to perform the odor assessment and complete a few demographic and health questions online. Participants do need access to the internet and a physical address to receive the scratch-and-sniff odor cards.

I encourage everyone to visit the Participate in Research page on our website and email us to join this study.

Q. How does this test differ from the many others out there to learn more about the loss of smell and COVID-19?

A. The main difference is that in this study, in addition to asking people to rate their sense of smell, we directly test their ability to identify everyday odors. Monell colleagues have found this direct testing method may be more accurate – their recent meta-analysis found that tests that ask participants to directly smell a sample odor reported 70 percent of subjects losing their sense of smell; however, self-report tests showed that only 50 percent of subjects claimed to have an olfactory deficit.

We are also using the same questions as the Global Consortium for Chemosensory Research Survey so that data from both studies can be compared.

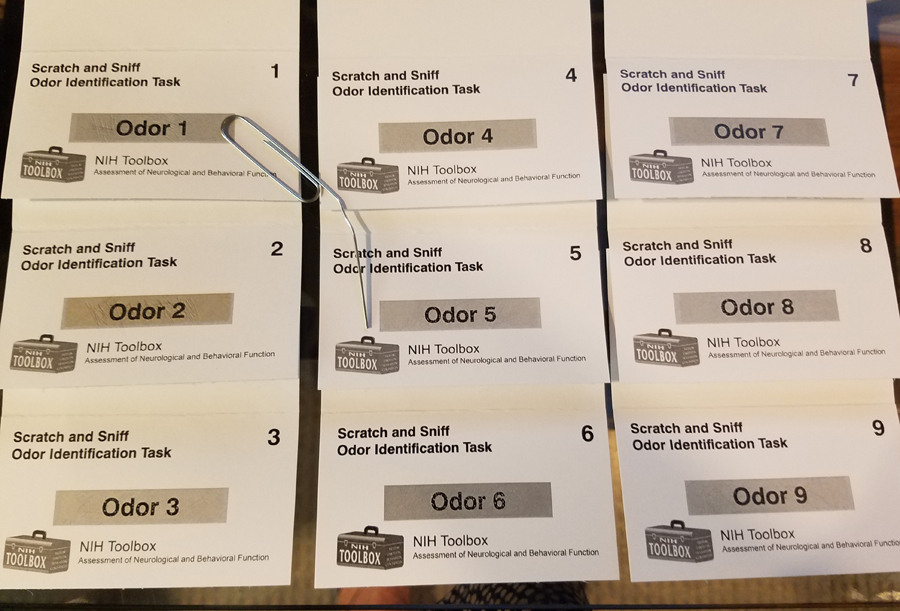

For this current scratch-and-sniff test, we are using the adult version of the NIH Toolbox Odor ID Test, which consists of nine microencapsulated odors placed on small, individual cards. The test was created as an off-the-shelf, brief, and inexpensive test to use throughout a person’s lifespan.

It was originally designed with the intention of being administered with the participant and the tester in the same room, but COVID-19 has made that impossible for the past few months. So we did further research, and I’m pleased to say we just submitted a methods paper that shows that this test can be successfully used at home to assess how aging or cognitive decline might affect olfactory performance.

Q. How does the test work?

A. Participants receive a letter with the odor cards, a link to the website, their code, and instructions on how to sample and make their online response. For each of the nine cards, the survey gives four possible responses as pictures with labels in English. Only one is the “correct” odor identifier. Responses are made by clicking on the chosen picture that corresponds to the odor card they are smelling, mimicking the way this test was originally performed in the Monell lab with an in-person tester.

Q. How have you used this test in the past?

A. We used this tool in a previous study in collaboration with the Brain Health Registry, a web-based, observational survey to gather information on the progression of neurodegenerative diseases and brain aging.

Q. When do you think you will be able to get back to in-person human testing, and what studies do you hope to focus on first?

A. All human testing at Monell has been paused since mid-March. We are in the process of developing guidelines for safely bringing participants back to the Center for in-person testing, hopefully in August. In some cases, studies have been modified to perform certain aspects of the research remotely. When that isn’t possible, we are instituting procedures to protect both our research staff and participants.

As an example, our lab’s study on natural gas odorants will resume with perhaps only two people tested at one time using our six-person olfactometer – allowing for physical distance. Another of our studies involves exposure to a workplace chemical in one of our chambers, and is already suited for the present situation: the participant spends six hours a day for two weeks completely isolated from our research staff.

Remotely, we are planning a study evaluating the ability of smell-screening to identify COVID-positive individuals even in the absence of other symptoms.

Q. There have been some articles in the popular press on COVID-19 quarantine smell habituation issues, meaning that since we’re spending more time in our homes, we are becoming immune to certain bad smells. What do you make of this?

A. When our odor receptors are repeatedly exposed to the same smells, they stop responding. Spending so much time in the same environment means that we are constantly smelling the odors within our homes.

Odor adaptation differs from such other senses as hearing. Most people can tune out a noisy street sound, but if they pay enough attention, they can bring those sounds back into their awareness. On the other hand, when we adapt to an odor, it smells much weaker or not at all, and we cannot will ourselves to smell it again. In fact, depending on how long we’re exposed to the odor, we may need days or weeks to recover our sensitivity to it.

Odor adaptation is specific to the odors you’re exposed to, so we wouldn’t expect it to affect our general ability to smell, but it might make some test odors less detectable.

Thanks for taking the time to answer our questions, Dr. Dalton!