After 27 years at McCormick & Company, William Zeiger, PhD, knows a thing or two about olfaction and taste. Zeiger began his scientific career as a Monell post-doctoral fellow in the early 1970’s, working on early olfactory binding studies in Robert Cagan’s biochemistry lab. After retiring in 2003 as Director of Flavor Research, he turned his focus to investing — an interest he also acquired at Monell during late-night discussions with the Center’s legendary financial administrator, Martin Bayersdorfer. Now, 40 years later, Zeiger finds himself returning to Monell and his scientific roots.

William Zeiger, PhD, Monell Alum and Supporter

William Zeiger, PhD, Monell Alum and Supporter

“After all these years, how we detect and process smells remains a mystery. As someone who started by studying in vitro olfactory receptors from Rainbow Trout, I am delighted to now be supporting the Center’s cutting-edge olfactory neuroscience,” said Zeiger.

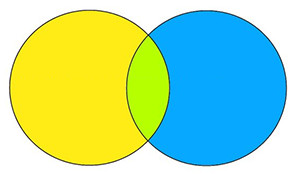

With a continued interest in olfaction, Zeiger was intrigued by a conversation with sensory neuroscientist Joel Mainland during a visit to Monell last fall. To help understand how the brain codes odors, Mainland is attempting to identify odor primaries — the set of basic odors that can be combined to create all perceived odors, much as blue can be combined with yellow to produce green.

Taking Zeiger into his lab, Mainland used a small device he had constructed — known as an olfactometer — to deliver suspected primary odors alone and in combination. Using the olfactometer, Mainland first presented four chemicals, individually, having odors reminiscent of grass, wax, fruit punch and caramel. Then, using the olfactometer to “blend” these odors, Mainland created a mixture that was identifiable as strawberry.

Back in Mainland’s office, the two continued their discussions on the topic of primary odors. When Mainland mentioned that he needed an olfactometer that could deliver 40 separate odors to test his theories, Zeiger knew how he could make a difference. Several weeks later, Monell received a check to underwrite the expensive piece of equipment.

For Mainland, the new olfactometer allows him to move forward and study increasingly complex odor mixtures. “This capability better reflects real world situations,” he notes. “Although most scientific studies of odor mixtures use only two odors, foods typically contain between three and 40 key food odors.”

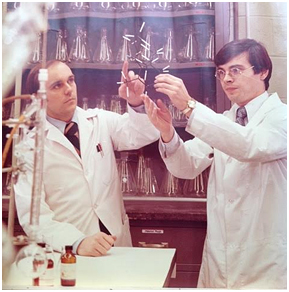

Reaching out to professionals skilled in combining odors to create food flavors, Mainland has asked several experienced flavor chemists for their suggestions of candidate primary odors. One of the flavorists he contacted was Robert Peterson, recently retired from Coca-Cola. Upon learning of this connection, Zeiger noted that he had hired Peterson over 30 years ago and forwarded a photo of the two in McCormick’s chemistry laboratory (Zeiger is on the left).

William Zeiger (left) and Robert Peterson in McCormick’s chemistry laboratory

William Zeiger (left) and Robert Peterson in McCormick’s chemistry laboratory

Zeiger’s interest in Monell’s olfactory research extends to the Center’s efforts to understand and develop treatments for anosmia. “The sense of smell is critical to how we are able to enjoy foods and live our lives,” he says. “From genes to stem cells, Monell has its finger on the pulse of the future and I’m excited to be involved.”