Monell is a unique organization; the only independent research center in the world studying taste and smell. I first found out about Monell in 2011 while walking my kids through the Philadelphia Science Festival Carnival. I was fascinated by smelling different odors and finding out that taste and smell are known as the chemical senses. I also found out that these two chemical senses are joined by another, chemesthesis, or chemical irritation (imagine the sensation you get after eating a hot pepper). Well, I love spicy foods so I got hungry for more information.

I connected to Monell on Facebook and started reading more about their history and research. Turns out, Monell’s first home was just blocks from where I grew up. I then found out that the iconic sculpture in front of the Monell Center, Face Fragment, was created by Arlene Love.

Face Fragment by Arlene Love

Face Fragment by Arlene Love

Arlene is an alum of Tyler School of Art, where I worked for 14 years, and a member of Tyler’s alumni board. I then read about Monell’s Founder Morley Kare, and was struck by the similarities to Tyler’s Founding Dean Boris Blai. Both were charismatic leaders (and great fundraisers!) who came to Philadelphia to build something out of no more than a good idea and a spark of innovation. Monell and Tyler are now both thriving organizations with international reputations.

I was quickly becoming a fan of Monell.

A couple of years later when I saw that Monell was looking for a director of development, I jumped at the opportunity. I had spent the previous eight years doing fundraising for an educational organization that works with many other Philadelphia organizations on STEM advocacy. This work taught me that expanding literacy in STEM-related fields will really fuel our future economy. My father, an allergist, had spent the early part of his career in biomedical researcher. My grandfather was also a physician. When I thought about my next move, I wanted it to be in a STEM-related field.

Now, nearly three years into my stint at Monell, I have learned more than I could have imagined. Recently, I was running through the scientific demonstrations that I took part in over the last year and was struck by how many “wow” moments I had experienced and yet how much more I still have to learn.

What follows is a lay person’s interpretation of some of my past year at Monell. My hope is that it provides a new look at the purpose and potential behind the discoveries being made in taste and smell and how these discoveries impact our lives in often surprising ways.

_____

If you attended a Monell event this year, you would likely have taken part in several scientific demonstrations and met some really interesting and smart scientists who are passionate about their work. Monell works hard to explain its science through these hands-on experiences. If you are like me, you found the “reveal” of the science to be intriguing and thought provoking. Read on and I hope that you get a broader understanding, as I have, about the journey from wow to real world impact.

BITTER TODAY, PERSONALIZED MEDICINE TOMORROW

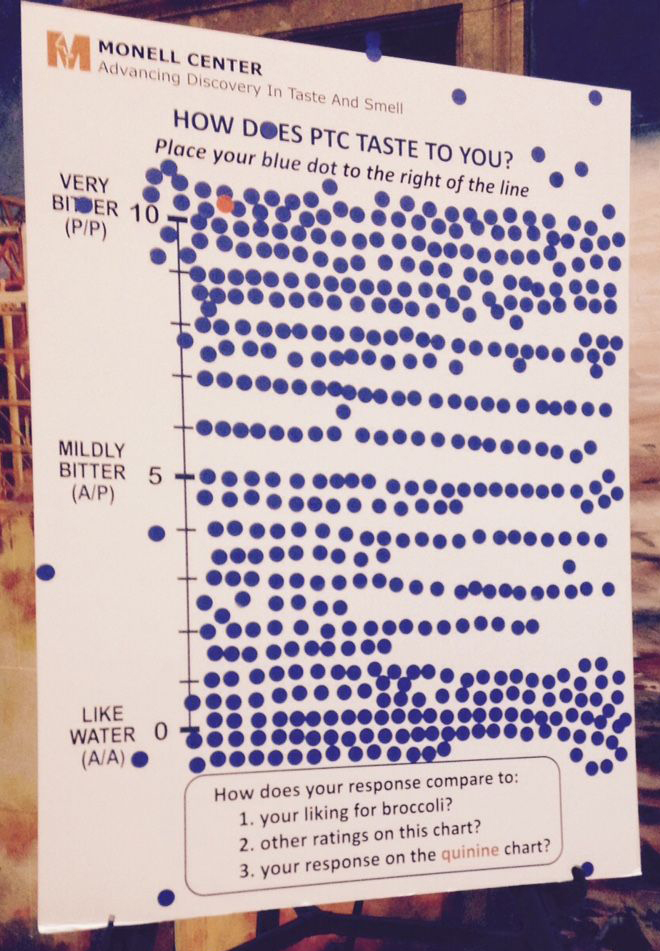

Last July, I helped organize a Gin & Tonic Happy Hour to introduce a small group of individuals to Monell. Together, a room full of about 20 people enjoyed drinks and snacks while Monell behavioral geneticist Danielle Reed talked to us about personal variation in how we detect bitter tastes, such as the quinine in tonic water. Dani then asked each of us to drink a clear liquid containing a compound called PTC and rate its bitterness. To me, the PTC tasted just like water. But, others were repulsed, even nauseated, by the bitterness.

Variations in perceived PTC bitterness – each dot represents a single individual’s PTC bitterness rating

Variations in perceived PTC bitterness – each dot represents a single individual’s PTC bitterness rating

Simultaneously, one of Monell’s lab managers examined our DNA to look at our individual genetic variations related to the taste receptor that detects PTC.

Later that evening, my genotype test came back and confirmed that what I had already learned from tasting the PTC, that I have the receptor type that makes me insensitive to this bitter compound. PTC is closely related to a chemical that gives cruciferous vegetables their bitter taste, so this probably accounts for my being able to easily munch on raw broccoli and enjoy other vegetables such as Brussels sprouts that many people find bitter. This was a fun demonstration about individual taste differences, but I wanted to know more about why I should care. Science Communications Director Leslie Stein explained to me that understanding taste differences today may one day lead to individualized medicine. How could this be possible?

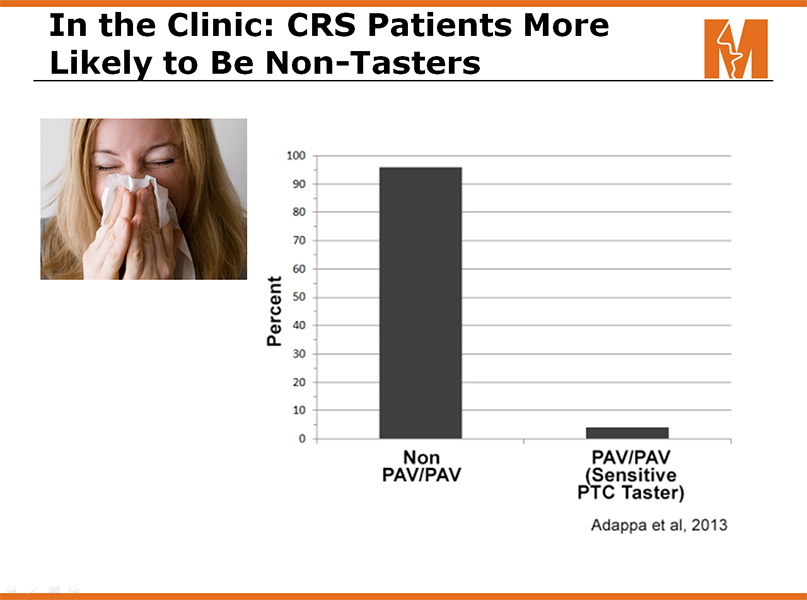

You see, taste receptors have now been found to live in other places besides the tongue. They are in your stomach, intestines, pancreas and even your airways. Dani Reed is collaborating with Monell faculty member Noam Cohen, a physician at the University of Pennsylvania, to understand the role of bitter taste receptors in our airways. What they are finding is that the PTC taste receptors in our airways serve as a sort of early warning and defense system against invading bacteria. People with the taste receptor genes that make them highly sensitive to the bitter taste of PTC also are better at detecting invading bacteria that cause upper respiratory disease, and they are better at initiating defensive responses to these invaders. That makes those of us who are not so sensitive to bitter, including me, more susceptible to diseases such as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and less responsive to some treatments.

CRS patients are more likely to be insensitive (ie “non-tasters”) to PTC bitterness

CRS patients are more likely to be insensitive (ie “non-tasters”) to PTC bitterness

This is a growing public health issue. In the United States alone we spend over $8 billion a year on healthcare costs related to CRS. Many of these costs are for one-size-fits-all treatments rather than informed choices based on our individual differences.

We expect that the discoveries being made by Dani and Noam will eventually lead to individualized treatment of diseases such as CRS. Imagine your doctor giving you a simple taste test, then using the results to prescribe a tailor picked treatment targeted to your particular genetics. In the long term, this innovative application of individual differences could reduce the number of unnecessary medical procedures and ineffective therapeutics, thereby lowering healthcare costs.

MASKING VS BLOCKING

In March Monell featured the science behind your everyday cup o’ joe at La Colombe Coffee Roaster’s new flagship location in Philadelphia’s Fishtown section. During the event, we offered guests four coffee-oriented science demonstrations, one of which helped attendees learn about the difference between masking and blocking bitterness.

Turns out, when you add sugar to coffee, it masks the bitterness. But, when you add a pinch of salt to your coffee, it blocks the bitter receptors. Masking means that the bitterness is still there but it is less noticeable. Blocking means that the bitterness is never experienced because the sensory signal never reaches the brain.

In this demonstration, Monell researcher Corrine Mansfield used a pinch of salt to reduce coffee’s bitterness

In this demonstration, Monell researcher Corrine Mansfield used a pinch of salt to reduce coffee’s bitterness

I know you are thinking that you really do not care about the difference between masking and blocking, but let me give you an important reason why we all should care.

It is common for manufacturers of oral amoxicillin, often prescribed for young children, to mask the bitterness by adding flavors and sweeteners. But, children still find these medications to be extremely bitter and unpalatable. Thanks to a unique new innovative technology developed at Monell, scientists envision a day when we can identify and block the taste receptors responsible for recognizing the bitterness of amoxicillin. This may yield a future when we can pharmacologically block amoxicillin’s perceived bitterness rather than trying to mask it. This would improve the acceptability of amoxicillin and other oral medications necessary for young children who cannot yet swallow pills or capsules.

If you have kids, I’m sure you have experienced the same dread and fear that I experienced when my kids were babies and would spit out their amoxicillin. Now imagine a time when the bitterness in the medicine is blocked, the bitter taste problem is ameliorated, the baby happily swallows its meds and quickly recovers, and the parent’s fear subsides.

What does this mean for the larger public? In high-burden countries where a treatable disease such as pneumonia means the difference between life and death, this innovation could eliminate hundreds of thousands of deaths (current estimates are 600,000 every year) in children ages one to five.

JELLY BELLY

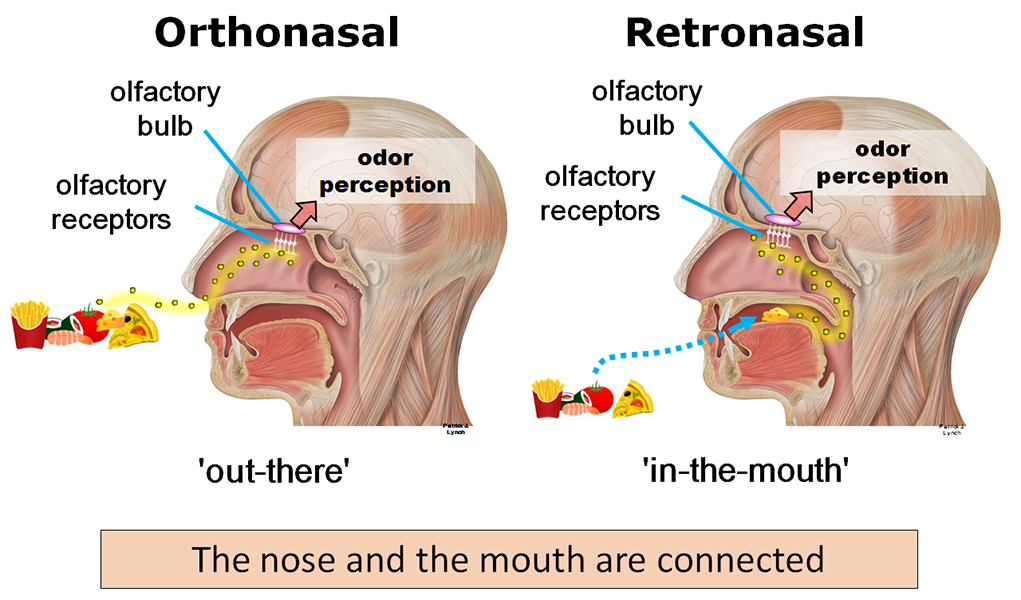

I’ve eaten countless jelly beans in the last year. Not because I like jelly beans more than the average person, but because they are a great way to understand how the senses of smell and taste are connected. The demonstration starts with two different flavors of jelly beans. Without looking, choose a jelly bean. Before you put it in your mouth, hold your nose shut with your fingers. When you chew the jelly bean, you will sense that it is sweet, but you will be unable to detect whether it is banana or licorice. Then release your nose and voila, you will experience the flavor.

When you hold your nose, you create a pressure gradient that prevents smells from traveling from your mouth to the olfactory receptors deep inside your nose. Because the receptors do not register the odors in your food, you do not fully experience flavor because flavor only occurs when the brain combines information about both taste and smell. When you finally release your nose, the receptors are able receive the odor information, and you sense the jelly bean’s flavor.

When you release your nose, odors travel from your mouth to your olfactory receptors.

When you release your nose, odors travel from your mouth to your olfactory receptors.

Cranium images adapted from the original by Patrick J. Lynch CC BY-NC-SA 2.5

This demonstration is powerful because it helps you understand what your world would be like without smell. The sense of smell is often taken for granted but when you do this demo, you will put yourselves in the shoes of someone who does not smell, and I think you will begin to feel more empathy for those suffering from this invisible disability.

I really look forward to my morning cup of coffee, a steaming bowl of soup or even a jelly bean after lunch. But, olfactory receptors can easily become dysfunctional, even by common occurrences such as a cold or a head injury from an accident. The result can be total loss of smell, or anosmia, which affects millions of individuals worldwide. People suffering from anosmia report lack of enjoyment for food.

But, the experience of anosmia is much more debilitating than not enjoying a meal. Those suffering with anosmia cannot smell gas leaks or alcohol on a person’s breath. They cannot smell the sweet scent of their own children. Anosmics report depression and anxiety, lack of personal safety and security, some even report lack of job security (imagine being a chef and losing your sense of smell!).

Since I have been at Monell, we have created a reason for hope for these individuals. With funding coming primarily from those who suffer from anosmia, Monell currently has a two-pronged attack to combat anosmia. We are looking at its basic mechanisms by studying genetic patterns in those with congenital (inborn) anosmia and we are harnessing the power of olfactory cell regeneration to study how new stem cell technologies could eventually be used to treat those with acquired anosmia.

If you’d like to learn more about those who live life without smell, please visit our anosmia awareness website.

____

I joined Monell with an interest in science but with little more than basic high school and college science classes. Thanks to my patient colleagues who have given their time and expertise, the science of taste and smell is becoming much clearer to me. I am beginning to form a more complete picture of the role of taste and smell in health, safety, and happiness in my own life and in the world around me.

I was prepared to learn something new at Monell. What I wasn’t prepared for was the profound and vast applications of our science. Beyond the three examples I’ve discussed here, other work at Monell has potential applications for diseases extending from ovarian cancer to Alzheimer’s disease to irritable bowel syndrome and even parasitic infections and migraines. One of my co-workers suffers from migraines so I am particularly intrigued by how Monell can make a difference for her and millions of others worldwide.

My experience at Monell makes me care about the chemical senses. And, it makes me a much stronger advocate for basic research into the senses of smell and taste.

If somehow I’ve put Monell’s science into new perspective for you, please continue to learn about Monell by visiting our website, connecting with us on social media, by attending our events, and by becoming a donor. Your involvement truly makes our discoveries possible.

Jenifer Trachtman

Director of Development